Problems

& Perspectives

#1

Lou Reed’s

Transformer, etc.

—————-

By Beppe Colli

Apr. 21, 2014

While out for a walk, I happened to see Lou Reed’s face – by then, he

had been dead for a few months already – looking at me from behind the

windowpane of a newsstand. I got nearer, just to check, and I saw a special

issue of a magazine – a "Ultimate Music Guide", "From The Makers

Of Uncut" – wholly dedicated to him. You know the formula: a series of

previously published articles and interviews dating from way back, plus newly

written record reviews, "A New Look At Every Solo Album". While the

old articles and interviews tell it "like it was", including the

enthusiasm, the missteps, and the (not-so)perceptive judgments on the part of the

music press, the new record reviews are perfectly aware of "what came

later", and of course knowing "what really happened" gives

reviewers a "prophetic spirit" that those who wrote at the time

obviously lacked. The "pragmatic" intention embodied in this way of

doing is quite easy to guess, with old articles giving readers the proper

background, and new record reviews acting as a kind of "consumer

guide" in the light of a more recent evaluation.

I wondered if the famous piece about Lou Reed "boxing" with David Bowie was included. Sure, here it was, announced on the cover as: "Lou vs. Bowie – A Ringside Seat At The Famous Fight". Appearing with the title "Don’t You Ever Fucking Say That To Me!", the article penned by Allan Jones originally published in the issue of U.K. weekly Melody Maker dated 21/04/1979 is reproduced here, starting from page 74.

Back home, I put on my leather jacket and a pair of very black sunglasses, and I started reading. My starting point? Well, Transformer, of course.

While nowadays it can be said that Lou Reed is famous for many reasons, things were quite different on the day the U.S. musician entered Trident Studios, in London, to record the album that, to everyone’s amazement, gave him his first, and only, real smash. While at the time The Velvet Underground were still "under the radar" as the proverbial "cult group", the album titled Lou Reed – his weak first solo effort also suffering from quite uncertain production – appeared to show the artist as ready to be consigned to a role of "has-been". Transformer was the album that changed Lou Reed’s life forever, giving him the perennial hit Walk On The Wild Side. Quite surprisingly, a song that at the time of the album’s original release sounded dangerously close to "lightweight pop" – think: "adult easy listening" in the manner of, say, Barbra Streisand – has turned into an evergreen, almost sparing Lou Reed the task of having to perform his one and only hit forever. The song in question being Perfect Day, of course, Lou Reed’s original performance on Transformer showing his vocals sailing perilous waters when it comes to intonation (and wasn’t Herbie Flowers’s tuba on the song Make Up intended to make Lou Reed’s vocal performance sound completely assured, his voice being in fact at times quite uncertain?).

"The greatest ever performance of Walk On The Wild Side can be found on Take No Prisoners, Lou Reed’s live album from 1978.". This is what Stephen Troussé writes at the start of his review of Transformer which appears on page 34 of the aforementioned magazine. It’s a respectable opinion, of course, save for the fact that it will direct unaware readers to a performance of the song that’s totally devoid of those very qualities – recorded sound, instrumental performance, succinctness, and a perfect balance of ingredients – which only justify the prestige of the original version: recorded at Trident, it clearly shows the contribution of all involved. Stingy in his praise – Mick Ronson is the only musician he mentions – Troussé even fails to highlight the instrumental contribution of Herbie Flowers, whose performance on both double bass and electric bass has no little part in the song’s eternal appeal. Quite peculiarly, Ken Scott’s name – Scott being the engineer whose work plays a large part in making Transformer sound captivating and rich with polychromy in spite of the fact that its raw material offers a quite limited palette – gets no mention.

What about David Bowie as producer, then? "Bowie’s hand isn’t so apparent, and the remoteness is possibly calculated to lend him authority: he exists on the album as pure signature.", which is one of those elegant phrases that are obviously the fruit of great intellectual effort; unfortunately, it provides readers with elegance in place of truthfulness.

So the moment had come for me to take off my leather jacket and my black sunglasses, and to reach out for an old DVD-V.

I‘ll clearly state that while my favourable opinion is based on a careful examination of just a handful of episodes in the series – those that, in alphabetical order, deal with albums by Cream, The Doors, Jimi Hendrix, Elton John, Pink Floyd, Lou Reed, Steely Dan and The Who – I believe that the videos going under the moniker Classic Albums offer a very good compromise between the exigencies of entertainment and those of sound information. Usually split in two parts – one that’s colourful and entertaining, the other serving more specialized interests – those episodes I’m familiar with offer unexpected rewards. Granted, the series only deals with names that, one way or another, can only be called "legendary" – which cannot really come as a surprise: who would sink money in presenting artists nobody has ever heard of?

Though there are a lot of "biographical and social" chapters, this doesn’t necessarily mean that the episodes lack solid technical information about actual musical instruments being played, also about recording and mixing, a good for instance being the tasty "dialogue" between Chris Thomas and Alan Parsons about the amount of compression applied at the mixing stage on a world-famous album such as Pink Floyd’s The Dark Side Of The Moon.

While I bet there are many who consider Elton John as a kind of musical joke, I have to say that the DVD-V that deals with his album Goodbye Yellow Brick Road offers quite detailed information about the composing, arranging, performing, recording and mixing stages, producer Gus Dudgeon and engineer David Hentschel soloing elements off the multi-track and elaborating on the individual components.

What about Transformer?

The funny thing about the episode in the Classic Albums series that deals with the Lou Reed album Transformer is that the narration is quite unevenly split when it comes to Lou Reed’s story and character on one side, and the album proper on the other. What’s more, all those pieces of the puzzle offered to viewers don’t succeed in presenting a coherent whole.

As it can be expected, a long chapter of the story is dedicated to The Velvet Underground – funny thing: John Cale is never mentioned – and to Andy Warhol, with precious minutes given to those figures from Warhol’s Factory Lou Reed talks about in his lyrics to Walk On The Wilde Side. A long examination of "Lou Reed as poet" and of his "three chords theory" don’t add much to our comprehension of the album.

What about Bowie? For inscrutable reasons, Bowie appears only very briefly in order to say something of no consequence. Maybe filmed at a time when he was already ill (the chronology is not very clear), Mick Ronson offers an exhilarating imitation of Lou Reed playing a "way out of tune" acoustic guitar, on which he performed those songs Ronson would later arrange, and present to those session musicians who performed on the album. Ronson does not discuss his arranging choices in depth, but others talk highly of his contribution to the album.

The main character on the album, and the writer of the "raw" songs, Lou Reed is shown trying to avoid things he maybe doesn’t want to clarify by jokingly referring to a "hash cookie" he accidentally ate after his arrival in the U.K. It’s apparent he didn’t even know about some arranging choices. It’s also apparent that some instrumental ideas and combinations were invented on the spot by those involved, to be later approved by Bowie.

When it comes to dealing with such albums as Transformer (or, as we’ll see in a short while, Coney Island Baby) two main approaches are involved: one that examines what’s on the album (definitely the less common approach); the other that builds a kind of fantastic entity that it then proceeds to consider as being "real" (this, it goes without saying, it’s what mostly passes off as criticism nowadays). An important feature of approach #2 is to perceive the existence of an "outside" contribution only when it’s obviously apparent (Bob Ezrin’s work on Berlin being a "positive" example, with Steve Katz’s work on Sally Can’t Dance as a "negative" example), with all that appears to be "simple" being perceived as a "self-starter". (I won’t deal with those who believe Lou Reed wrote the instrumental parts, and the arrangements, of his album Berlin.)

For brevity’s sake, I won’t deal with the issue of authorship when it comes to the instrumental parts which appear on the Transformer track Walk On The Wild Side (here the DVD-V speaks for itself). We don’t usually perceive the more "technical" type of contribution – and luckily so, otherwise a piece wouldn’t work. But without that contribution a piece would not work as well as it does.

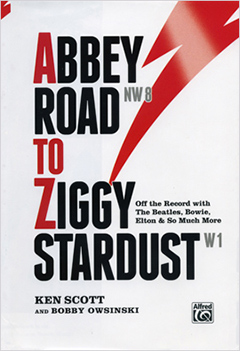

The Transformer DVD-V shows sound engineer Ken Scott highlighting some instrumental passages that were later included, or discarded. What’s not really clear in the DVD-V is the "chain of command". Here we can check those few pages that a recent volume dedicates to the Transformer recording sessions. The author? Ken Scott.

At the time, Ken Scott was already considered to be a very competent engineer. But it was his producing and recording work on such Bowie albums as Hunky Dory and The Rise And Fall Of Ziggy Stardust And The Spiders From Mars that made him a well-regarded producer and engineer.

Just like it’s useful to see Mick Ronson’s arranging work on Transformer in the light of what he had already done on those aforementioned Bowie albums, the same is true when it comes to the work of Ken Scott.

It’s obvious that listing Bowie and Ronson as the sole producers of the Transformer album, so excluding Ken Scott, was meant to give a stronger impression when it came to the involvement of David Bowie, the star. It goes without saying that Bowie’s contribution to Transformer was larger than his actual involvement to the All The Young Dudes album by Mott The Hoople – save for the fact that Bowie gave the group the song that gave them a new lease on life.

But one can’t help but smile when reading that Transformer was mixed by Ken Scott, Mike Stone, Lou Reed (!), David Bowie, and Mick Ronson. Bowie had already left, by ship, for the United States, Ronson participation to the mix was limited to a single session, and Lou Reed "was not really there"… (see: "the hash cookie", above).

Let’s have a look at the way the very famous female vocal parts of Walk On The Wild Side were given shape in the mix. This is Ken Scott from page 168 of his book: "By the time it came to mixing "Wild Side", I was so sick of hearing the "doo doos" so many bloody times that I had to do something just to relieve the boredom of it. I had this idea of them coming from way back in the distance and walking forward finally singing it right in your face. I started off with just the reverb signal which I kept at the same level during the mix, but I had the source background vocal level come up and up until you hardly hear the reverb at all and they’re almost dry and in your face."

This will be all the more apparent the more the copy in our possession resembles the original album.

A simple, sparse work – and in a way, that’s exactly what it is – Transformer is not an "elementary" album. The song sequence on the LP sides offers a variety in style and sound that makes one listen "actively". Even a song like Walk On The Wild Side is a lot less static than it could appear to a lazy ear – check the way Lou Reed’s voice changes the moment he sings the famous "doo doo" that precedes the first appearance of "the colored girls", and the way this creates the continuity the makes this transition plausible.

But nowadays the fact of a new edition resembling the original is not to be taken for granted, this being especially true today, when digital files of unknown vintage are available to be bought online.

I compared a German vinyl pressing from the early 80s – not the very best, admittedly, but still well within the analogue master stage – and a CD edition from 2002 from the Original Master series Made in the EU. Compared to the LP, the CD sounds more compressed, and the effect is quite easy to perceive, especially so when it comes to such acoustic instruments as the double bass, also the lack of the sense of "surprise" one gets when the instrumental volumes continuously vary. Of course, listening to the CD in a car will give better results. However…

Let’s go back for a moment to the Uncut special issue. Let’s check the review of the album Coney Island Baby penned by Peter Watts which appears on page 50. As per his intro, Watts quotes part of what Lou Reed said about the way the album had its start as stated in the booklet of the 2006 CD edition of the album. Here’s the close of the Lou Reed statement: "Then Ken Glancy called and told me ok, pick a studio and go in and make a rock record. And so I did."

Which is all true. But entering a studio doesn’t necessarily entail fine results, and when it comes to the album in question it’s apparent that a large part of its success can be ascribed to Godfrey Diamond, who produced the album.

The main spread of the booklet that appears in the aforementioned 2006 edition of Coney Island Baby features as its spread the historical review of the album penned by famous critic Paul Nelson, who hailed a reborn Lou Reed (in a period immediately following the Metal Machine Music imbroglio) from the pages of what was at the time the most influential music magazine in the world: Rolling Stone. It won’t be a surprise to those who are familiar with the work of the late critic that his analysis is almost entirely centered on the song lyrics. (Come to think of it, wasn’t Lou Reed a poet?)

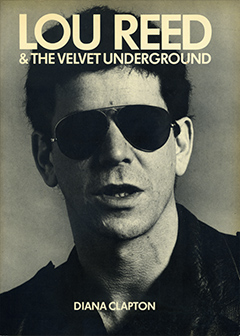

Here we can check Lou Reed & The Velvet Underground, by Diana Clapton, an old volume printed by Proteus in the pre-Internet era, where the chapter that deals with the album Coney Island Baby quotes at length producer Godfrey Diamond. Recorded in New York famous Mediasound studios, the album sounds so fresh thanks to the sound chosen by the producer – "Then, I was into tight drums, tight R&B, no ambience" – also to the fact that he managed to keep the album within a coherent frame: "We did have something of a discussion on Street Hassle and I Wanna Be Black. I felt both were excellent, but they did not belong on this album." (…) "Street Hassle was brilliant but it wasn’t hooky and it was far too heavy. I couldn’t let him slip back into that weird tone head. I had to give him another Walk On The Wild Side."

Not taking Diamond’s contribution into account also makes it impossible for one to understand what happened later, with the album Rock And Roll Heart, recorded by Reed not long after Coney Island Baby in an excellent studio such as the Record Plant in New York with the aid of the same band, more or less, that had so brilliantly contributed to his previous album. The new album sounded like it was recorded on a piece of cardboard, with no arrangements, songs sounding flat, no dynamics. The songs are not so different from the ones that appeared on Coney Island Baby. But now the producer was Reed himself, who also did the mix together with two engineers, for what was his first album of his new contract for Arista, a new label of which Clive Davis was president. Was his "poetry" that had changed?

© Beppe Colli 2014

CloudsandClocks.net | Apr. 21, 2014