An interview with

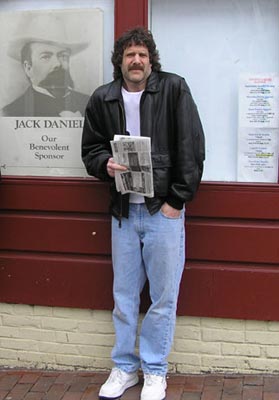

David Simons

—————-

By Beppe Colli

April 19, 2005

As

I recently argued in my review, Studio Stories by David Simons (Backbeat

Books, 2004) is practically required reading for those who want to know

more about a slice of an important history: that of those big,

and glorious, recording studios that are for the most part now becoming

history.

I though that having a conversation with Simons about some of the

themes that appear in the book was a good idea, so I got in touch with

him via Backbeat Books. The conversation that follows was conducted

by e-mail, last week.

As a first thing, I’d really like to know about your background.

On the cover of your book it says that you’ve written, among others,

for Musician, Home Recording, Guitar One and Acoustic Guitar. Could

you please give me a fuller picture?

You mean in addition to scribbling trash for the publishing world?

I’d spent a good deal of time in bands over the years, but eventually

I got tired of that and about five years ago I started putting together

a recording studio in the basement here, bit by bit. The cool thing

was that along the way I was able to take whatever information I’d glean

from doing interviews and put it to use in the studio (like when Todd

Rundgren mentioned that he always rotated the snares so that they were

parallel to the drum mic, etc. etc.). So that became a mild obsession,

and eventually it grew into a miniature mock-up of a real studio, with

a small control room and adjacent recording room. Later when I finished

Studio Stories, I was so pumped from listening

to all these old codgers that I went and built a live echo chamber right

off the drum room – which I admit is pretty extreme, but honestly it

sounds better than any of my digital stuff.

Tell me more about the idea behind the book.

While at Home Recording magazine I’d done a few pieces

on some of the great old studios like 30th Street in NY and Western

in LA, including interviews with the original engineers, notes about

famous songs/albums, etc. At the suggestion of my editor, Rusty Cutchin,

it turned into a mini-series called Studio Stories. I stopped after

about six installments, but I thought it had the makings of a decent

book, so I pursued the idea. It was originally supposed to cover all

these different regions of the U.S., but after Jim Cogan put out Temples

of Sound (which was very nicely done) I thought it would be best to

do something totally different, so I decided instead to focus on one

particular location – New York. Which, in hindsight, worked out much

better anyway.

The thing is, I didn’t want it to be just a straight technical read

(although I love that kind of info myself), because I knew there would

be some really nice historical/cultural undercurrents that would be

at least as important as all the stuff about mics and consoles, etc.

So my goal was to present a series of stories about New York’s studios

and music scene during this 30-year period that would be loosely connected

by a main theme – the spark of ingenuity that marked the early and middle

years of modern recording, and the subsequent loss of innovation that

was the result of too much technology (and the ultimate streamlining

of the whole record-making process).

"Great Sounding Record" is of course a pretty subjective

notion, but I have to confess that the only "great sounding record"

I’ve listened to in recent times is Get Away From Me, the debut album

by Nellie McKay produced and engineered by Geoff Emerick – recorded

at Clinton Recording Studios in New York, mixed at Capitol Recording

Studios in L.A. Are you familiar with this CD (and those studios, of

course)? Other "great sounding records" you’ve listened to

in recent times?

I haven’t heard Nellie’s entire album, though I did like the track

David quite a lot – nice song and interesting production job. But until

very recently it’s been like torture to try and sit through more than

five minutes of mainstream radio. We had a nice period back around ’93-96

with the return of guitar-oriented rock along with some really tasteful

record production from people like Rick Rubin and Brendan O’Brien. But

right after that came all this doofus nu-metal, and guitar sound and

dynamics went right out the window. Every once in a while you’d get

something great like Weezer’s Green Album, which was absolutely fantastic-sounding,

or stuff by Foo Fighters, or Rage and later Audioslave, but those were

exceptions.

I’m a bit puzzled by the peculiar kind of "progression"

of "home playing equipment" – from the record players that

were mostly used to play singles to "real hi-fi" systems to…

computers and, nowadays, iPods. It seems to me that nowadays people

prize affordability (which sometimes means "free"…) and

portability over sound quality and attention to detail. Judging from

your personal experience, have you noticed a shift in people’s patterns

of consumption?

I think the popularity of digital music services like iTunes and

Napster is proof that music will never again be a completely tactile

commodity. I mean, there’s no denying the benefits of digital portability

– let’s face it, having the ability to cart around your entire record

collection in an MP3 player the size of your shirt pocket is pretty

enticing. Obviously, though, the transformation of music from a physical

medium to a bunch of bits and bytes, not to mention the infinite selection

offered by Internet music libraries, has made music increasingly disposable,

as we grow accustomed to downloading and listening, then quickly deleting

and repeating. Which isn’t necessarily such a bad thing.

Sometimes it’s easy not to notice the amount of work needed to

achieve something – my favourite example of this being Chris Thomas’s

production of the Sex Pistols LP. In your book you interview Ed Stasium

about his work with The Ramones. Would you mind talking about this?

When you listen to those records, you know there’s something really

good going on but you can’t really put your finger on it right away.

And it’s because they have this great vibe, and I think that Ed had

a lot to do with that. Besides being a great record producer, Ed is

also a real character, and he was very forthcoming about what went on

during those sessions. For one thing, there’s this notion that the Ramones

were just a bunch of amateurish scrubs, which is completely wrong –

they had a great love of pop music, they knew so much about songwriting

and record making. And Rocket to Russia was a really concerted effort

to put together a commercially successful pop album. What Ed and Tommy

(Erdelyi) did at Mediasound during Rocket to Russia – and later

Road to Ruin – was absolutely amazing. You compare it to the first album,

which was cut at Plaza Sound above Radio City Music Hall – it sounds

great, though in a dry, padded-down sort of way. But then you put on

Rockaway Beach or Teenage Lobotomy from the third album, and you can

hear what Ed was trying to do with room sound and overdubs – Johnny’s

guitars still sound thick and live, but there’s also this extra sheen

from the layering and ambience. And it’s not like, "Oh, they’re

doing a bunch of overdubs here," because you don’t really notice

it – you just hear that something’s different, there’s this atmosphere. That’s what makes

guys like Chris Thomas and Ed Stasium unique.

Once upon a time it was sometimes possible to guess in which studio

a song had been recorded just by listening to it on the radio (I remember

the sound of the piano recorded at Trident Studios appearing on several

albums during the 70s). Did it ever happen to you?

Actually, from doing this book and related articles, I started getting

pretty good at picking out what was recorded where, to the point that

I could be a real annoyance while driving around with my wife with the

radio on. In the book a lot of the engineers talk about this phenomenon

– which was mainly due to the "homemade" aspect of the old

studios and the recording techniques of the time. Back then, most of

the really fine studios had their own hand-made echo chambers and recording

consoles, or the rooms were constructed in a unique manner, and so forth.

Each studio had a dedicated engineer; some even had an R&D department

that put built equipment in-house. Others had a house band that supplied

the backing tracks for most of the hits recorded in that particular

studio. So all of these elements combined to give a studio its signature

sound, which you can still hear on the radio today. It’s the complete

opposite of everything you have now – by and large everyone’s using

the same basic equipment, the same processing, plug-ins, etc. It’s like

having a hamburger from the local diner, versus a hamburger from McDonald’s.

Frank Laico was in many ways an innovator in production and engineering,

but his name is not as well-known as that of other producers/engineers.

So, for the benefit of those who haven’t read your book, would you mind

talking about him?

I’d been a great admirer of Frank’s since I was a kid – I always

loved the sound of those Columbia vocal recordings. Put on the radio

around Christmastime, and you can bet that every other song you hear,

Frank recorded. It took me years to figure out what it was about those

records that sounded so great – but in reality, it was the way he miked

up that huge room at 30th Street Studio, and of course that incredible

echo-chamber sound on those vocal tracks. He was really one of the first

to use natural room ambience and natural echo in a totally creative

way. It wasn’t something just anyone could do – Roy Halee, who was no

slouch, was spooked by the enormity of 30th Street, which is why he

admired Frank for being able to get such a sound in there. And it was

amazing, because not only could Frank capture this big, live element

on tape, at the same time all the different instruments had this incredible

clarity. Listen to any of those Tony Bennett records from the late ’50s

and early ’60s and you’ll see what I mean. And all he did was use some

really good condenser microphones placed in the right spots, with very

little processing – they were totally organic recordings.

Above all, Frank is a fantastic individual. He actually helped me

set up the echo chamber in my basement – he even gave me an old Western

Electric mic from Columbia’s Studio A to put in there. Can you believe

it?!

For your book, you also interviewed Roy Halee. Of course, his

Simon & Garfunkel sessions are what he is mostly known for, but

I have a fondness for the wet, mysterious sound of Laura Nyro’s New

York Tendaberry. Are you familiar with this album?

I’ve heard bits and pieces, and it’s been a while. My other favorite

Halee production is Hums of the Lovin’ Spoonful – his first real artistic

engineering job. A warm-up for the S&G stuff.

The last song you mention in New York Grooves, the last section

of your book, is one by Stevie Wonder, recorded at The Hit Factory in

1976. Of course, The Hit Factory closed its doors just a few months

ago. There are quite a few heated debates going on right now on the

Internet, and many theories about the (musical) reasons why so many

fantastic studios are going down. Would you please give me your opinion

about this?

This whole business – the demise of the "traditional" studio

– is really the main thrust of Studio Stories. Why is this happening?

It’s complicated and there are a number of reasons – in New York, for

instance, property values have skyrocketed over the past several decades,

and therefore a number of great studios became hot real-estate targets.

But in reality, the first nail in the coffin was the downsizing that

began during the rock era, when it became apparent to the industry heads

that a monstrous room wasn’t required to cut a pop combo. Then came

digital, and suddenly you didn’t need things like big echo chambers

or plates, you could just digitize all the effects, and things got smaller

still. And then with hip-hop and techno, everyone starting going direct,

and at that point you didn’t even need a room – you could cut a record

in a closet if you wanted. So it became this vicious circle, where the

technology began dictating the type of music produced, and vice versa.

Of course, along the way you still had people like Jon Brion and Jim

Scott who preferred "classical" recording techniques, and

in some small way helped preserve some of these older studios, I suppose.

But has it been enough to keep them in business over the long haul?

Apparently not. Look at what’s happened in the last few weeks alone

– in addition to the Hit Factory, we’ve lost Cello Studios in L.A.,

as well as Muscle Shoals Sound in Alabama. The quote from producer Lou

Gonzalez that closes the book – "you picked a good time to put

out this book, another year and there might not be anything left here

at all" – seemed a bit far-fetched at the time, but in reality

it may not be that far from the truth.

Something about future projects of yours?

Because of my semi-masochistic obsession with decrepit analog things,

my publisher thought it would be a good idea to do a book for those

who are curious about the stuff (tape machines, old pre amps, compressors,

reverbs, anything with tubes), with the idea of integrating into an

otherwise all-digital studio. Part I will be about the gear – where/what/how

to find, etc. – as well as principles of DIY analog, such as building

your own live chambers, heh heh. Part II will be a blow-by-blow account

of an actual basement recording session in progress, in which all of

the above tools & rules are put to (hopefully) good use. No title

as yet.

Then after that I’m most likely going to launch into a Studio Stories

2, this time about the West Coast. That should be fun.

(P. S. Last week I got a call from Elliot Mazer, who wants to put

together a New York recording history presentation based on Studio Stories

at the AES 2005 Convention in NYC. Elliot wants to invite as many of

the people who were featured in the book to take part in the presentation;

they’ll have a stereo rig and multimedia system on hand so they can

run music from the various studios along with a slide show depicting

shots of the artists, rooms, etc. A number of people have already indicated

they’d take part. Awesome, huh?)

© Beppe Colli 2005

CloudsandClocks.net | April 19, 2005