An interview

with

Michael

Cuscuna

—————-

By Beppe Colli

Nov. 2, 2008

Though in retrospect they are often seen

as a dry decade (and a period of sterile self-indulgence), at best just

good enough to function as a "guilty pleasure" under the "ironic" light

of "it’s so bad, it’s good", the Seventies were a long period

of stunning creativity, a true moment of "embarrassment of riches".

This being true of both jazz and rock.

It’s true that it was only at the end of

that decade that the (so-called) "Punk-Jazz Connection" (whatever

that means) appeared, but I think it can be said that – though the latter

phenomenon, being "urban and American", got a lot of pages at

a time when press still mattered – it was in the earlier period that both

rock and jazz attained peaks of formal audacity that in many ways have

yet to be surpassed (at least, by something sounding as fresh).

Though obvious reasons of cultural nature

have contributed to this fact being consigned to oblivion, it was mainly

rock fans in Continental Europe – already accustomed to the music of Frank

Zappa, King Crimson, Faust and Henry Cow – that greeted with much enthusiasm

the most daring experiments of US jazz musicians, showing no outrage when

seeing the obvious links to "non-jazz" precursors.

In that time period, Anthony Braxton was

a star. A special talent, sure, but it was also thanks to his being under

contract to a mini-major of those times: Clive Davis’s Arista. It’s a period

spanning (more or less) six years, from the sessions featured on New York,

Fall 1974 (where a daring jazz quartet is followed by a saxophone quartet,

and a clarinet/synth duo) to the composition appearing on For Two Pianos.

Flanked by those albums are the quartets on Five Pieces 1975 and The Montreux/Berlin

Concerts, the multifaceted Creative Orchestra Music 1976, the interrelation

with Muhal Richard Abrams on Duets 1976, the difficult-to-describe (but

not to listen to) For Trio, the Alto Saxophone Improvisations 1979, and

the monumental For Four Orchestras. All material appearing in the recently

released Mosaic Records box set obviously titled The Complete Arista Recordings

Of Anthony Braxton.

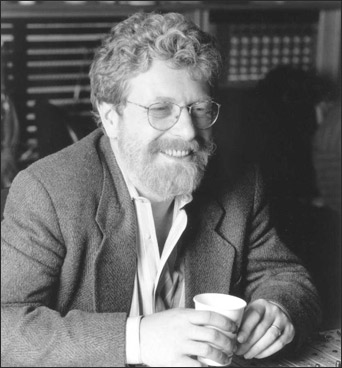

A co-founder of Mosaic Records together with

the late Charlie Lourie, Michael Cuscuna is a Producer whose name any jazz

fan worth his/her salt has seen at least once on the cover of a much-loved

album (often alongside Executive Producer Steve Backer): Fanfare For The

Warriors by The Art Ensemble Of Chicago, Lester Bowie’s albums on Muse,

those on Arista Novus (think: Air and Muhal Richard Abrams), Braxton on

Magenta… and on Arista.

I asked him for an interview, he accepted,

and the interview was conducted by e-mail, last week.

As a first

topic, I’d really like to know a bit about how you developed an interest

in jazz, and music in general; also about the circumstances accounting

for your transition from "fan" to writer and critic.

When I was about

10 years old, I started taking drum lessons. I loved R & B – Jackie

Wilson, Ray Charles, The Coasters etc., but started listening to Gene Krupa-Buddy

Rich and Art Blakey records for the drum solos and eventually began to

listen to and appreciate the music played before and after the drum solos.

I later took

up the saxophone but could not improvise. So when I was in college, I began

doing jazz on the university station in Philadelphia, working in a record

store, meeting musicians and eventually writing for Jazz & Pop, Down

Beat, Rolling Stone etc. through contacts that I had met. I also started

to produce a couple of concerts and tried to help some groups that were

without managers – Paul Bley’s trio and Joe Henderson’s sextet.

But I really

wanted to produce records so I got lucky when Buddy Guy with whom I had

become friends asked me if I wanted to produce his last album for Vanguard.

We did another one for Blue Thumb. Then I produced some singer-songwriters

Chris Smith and Bonnie Raitt, but during and after college I was offered

high paying jobs as a disc jockey on free form FM underground rock radio.

At the end of

1971, free form radio was gone and all the FM stations had formats and

playlists. So I quit radio. It wasn’t fun or creative anymore. An old friend

from Philadelphia Joel Dorn was looking for an assistant so I joined Atlantic

Records as a staff producer. I got to work with a wide variety of artists

from Dave Brubeck to Oscar Brown Jr. and was able to convince Atlantic

to sign the Art Ensemble Of Chicago.

I’m positive

that the first time I saw your name was as Producer on an album by The

Art Ensemble Of Chicago, Fanfare For The Warriors (a fantastic album,

by the way, and one of the first jazz albums I ever bought). I’d like

to know about how you came to know Anthony Braxton’s music. What did

you think of it?

I was corresponding

with Bob Koester and Chuck Nessa at Delmark Records and they sent me the

first AACM albums they made. It all fascinated me and I even took a trip

to Chicago in the summer on 1968 to meet and hear a lot of the musicians

like Joseph Jarman, Roscoe Mitchell and Muhal Richard Abrams. I didn’t

meet Anthony at the time, but loved his first Delmark albums. All of the

Chicago guys each had their own conception and sound and were so new and

different than the New York avant garde. I became a fan of so many of these

musicians.

I think that

the first Arista album that I bought was The First Minute Of A New Day,

the first one on that label by Gil Scott-Heron and Brian Jackson. Later,

I bought Patti Smith’s first album, and an album by Lou Reed. The first

Braxton on Arista that I bought was Five Pieces 1975. It always looked

strange to me that somebody like Clive Davis would start a jazz subsection

of a label that was obviously meant to be "commercial", and

that he signed somebody whose music was as uncommercial as Braxton’s.

Talk about that.

Clive Davis was

trying to build a major label quickly. So that meant signing established

artists like the Kinks or The Grateful Dead and signing cutting-edge artists

who had potential like Patti Smith and Gil Scott-Heron. It also meant having

a full range of music so he made a deal with Steve Backer to start a jazz

division. The Brecker Brothers were a success quickly and Clive allowed

Steve to sign artists like Anthony Braxton as long as they brought good

reviews and prestige to the label. I had convinced Anthony to move back

to New York because I had offers for him from both Atlantic and Arista

Records and I felt these opportunities might go away if he did not take

advantage of them immediately. He chose Arista because Steve was so honest,

believing and committed.

I think it

can be said that when seen in a "jazz framework" Anthony Braxton

appeared as a bizarre figure: he had studied mathematics and philosophy,

played chess, smoked a pipe, and had strange diagrams for his song titles.

Do you suppose that his being such an "unusual" figure for

jazz played a part in the amount of attention he got from the press?

Or was it just Arista’s promotion dept. at work?

I think it was

a combination of both. Anthony was getting known in jazz and contemporary

classical circles and was very clear about what he wanted to accomplish

from the beginning. I think it also helped that he was one of the first

AACM musicians who played with nationally known and established jazz musicians

instead of just forming groups with AACM members. His exposure with Circle

(Chick Corea, Dave Holland and Barry Altschul) really helped him.

Steve strongly

believed that this music could be accepted far better than it had been

and worked hard to market this music and prove that it could sell well.

I don’t have

a clear idea of the way Braxton was considered in the "jazz press" proper,

though I have the impression that his (three) quartet albums and his

Creative Orchestra Music 1976 were greeted with a certain amount of enthusiasm.

Am I wrong?

Yes, his three

quartet albums and Creative Music Orchestra albums were greeted with raves.

Critics who did not like or understand his music just didn’t write about

him.

If we consider

the material he recorded for Arista, I think it can be said that his

For Trio album is the moment when things changed. Coming from a "rock"

background, when listening to For Trio I had only to determine if I liked

that album, not whether it adhered to any accepted notion of what "jazz"

was supposed to be. What was your perception of the way the jazz press reacted

to it?

I don’t remember

what the reviews were like for this album. I’ve never been interested in

what other writers think and, to this day, I rarely read reviews. I think

features and interviews give the reader so much more.

I only got

to know about the For Four Orchestras album by chance, and the very existence

of the album For Two Pianos remained unknown to me until I bought the

Graham Lock book, Forces In Motion, a few years later. So I assume that

at that point Arista was not interested anymore, right?

Anthony’s sales

were slowing down but this was because the jazz public had a resistence

to projects like these which were totally composed. As long as Steve Backer

was there, Arista was interested. When he left the label, it was right

around the time that Anthony’s contract ended. So Anthony did not resign

and other artists that Backer signed went elsewhere as well.

I’ve always

been curious about the kind of contract that Braxton had signed. I mean,

at first I thought that he could only record for Arista, but then I bought

albums on Moers Music and Hat Art while he was still signed to Arista.

Could you talk about this?

Those albums

on other labels that were recorded while Anthony was on Arista came out

after the Arista deal was over. His contract was exclusive. The material

on Moers or Hat Art were cases where labels approached Anthony later with

existing tapes and made deals with him to release the music.

I became aware

of Mosaic Records thanks to the first Thelonious Monk box set (but too

late to get it!), and I’m the proud owner of the second Monk box set,

and of two Mingus box sets. Though I assume by now the story of Mosaic

to be well-known, could you please give me a compact picture?

Well, in the

early ’80s the record business was in very bad shape. My friend Charlie

Lourie who had worked at Blue Note and Warner Bros. and I were both out

of work. We made a proposal to EMI to relaunch Blue Note but they were

not yet ready to add a jazz division. Part of the proposal was box sets,

specifically The Complete Blue Note Recordings Of Thelonious Monk. At some

point, I realized that if we made these limited editions and sold them

via direct mail only, these box sets could be a business in and of itself.

So we started Mosaic Records.

If I remember

correctly, years ago I was asked what box set I would like to see (and

buy!) on Mosaic. I immediately wrote "Braxton on Arista", since

in my opinion this was first-class material that in a way defined an

era. But at the same time I was aware that – when seen in the context

of what’s considered to be

"accessible" – this music is really bizarre, and quite difficult.

Francis Davis has talked about "Ornette Coleman’s Permanent Revolution".

So I was really surprised to see this box set go on the drawing board, and

now on sale. How risky a choice is it? Has the mainstream changed?

It is not risky

in the sense that we will break even if we sell only 1000 sets. But of

course we need every set to be profitable to pay salaries and costs. I

think the set will do just fine. I had been trying to license this and

other Arista material for a long time. But I never got an answer from the

licensing people at RCA which had bought Arista. Then Sony and BMG merged.

I had a good relationship with the Sony people and they were able to set

up the deal to license Arista material. So I don’t think the mainstream

has changed. It was just a matter of finding people who would get the deal

done!

As for my

last question, I’d really like to ask you about memory. I mean, what

Mosaic is doing is to preserve "important cultural artifacts" in

a

"physical" format. But, as you know, the "spirit of the age" goes

in the opposite direction: impermanence and lack of memory, except for "nostalgia".

Scanning the horizon, what’s in store?

There is so much

great recorded jazz in the 20th century that we will never be

at a loss from projects from all eras of jazz. We are going to continue

to produce important physical documents of this music. We are also going

to start a series of LPs as well although the LPs and LP sets won’t mirror

the large CD sets.

I’m sure there

is a small jazz audience for downloads, but most jazz fans want documentation,

photography and information. I think physical formats will be with us for

a long time.

© Beppe Colli 2008

CloudsandClocks.net

| Nov. 2, 2008