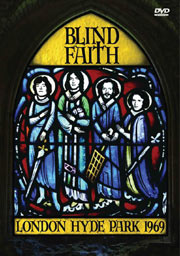

Blind Faith

London Hyde Park 1969 (DVD-V)

(Sanctuary)

Who

knows which group, artist or career would be considered today as deserving

the title of "great swindle in rock ‘n’ roll" – or in hip-hop,

or whatever genre. Above all else, who knows whether the prevailing

criteria of today even contemplate the possibility of something being

called a "swindle". In distant times everything was a lot

simpler: in the 60s there were the Monkees, who only pretended to play

their instruments, their records being the product of the work of the

best sessionmen (and one sessionwoman: Carol Kaye on bass) in California;

in the 80s, it’s Milli Vanilli who come to mind, pretending to sing.

But things have changed. On one hand, the fall of a kind of ethics one

could call "Puritan-Countercultural" made it possible for

one to accept and redefine the role and contribution of studio musicians,

from the first album by the Byrds to those albums by the Beach Boys.

On the other hand, the fact that the concept of "reality"

has morphed into "entertainment" makes the existence of a

"reality" that is different from the one that’s perceived

by an observer (any observer?) an impossibility. So, in these times

of "mechanically adjusted voices" (the "autotune"

which performs miracles even on those who are deaf and mute) and of

whole shows on hard disk (so as to make it possible for the dancers

– including the group – to save their breath for what’s really important:

the magic for the eyes of a screen-enhanced choreography) who could

ever dream up a slogan such as the one by Memorex from all those years

ago? "Is it live, or is it Memorex?". "But Melissa couldn’t

tell". (Maybe it’s necessary to remind the reader we are talking

about audio cassette tapes. If I’m not mistaken, Melissa was singer

Melissa Manchester.)

To

think that for many years the name Blind Faith was almost synonymous

with "big swindle" is quite funny. First, because the name

of the supergroup of UK celebrities (or at least, three celebrities

plus one) is today unknown to most, but not for reasons of ignominy

derived from moral reasons. Then, because the musicians in Blind Faith

were among the most serious in the whole United Kingdom. So?

Let’s

read the dialogue between an objective observer such as the late Timothy

White and a member of the group, Steve Winwood. Says White: "(…)

the Blind Faith tour was one of the tackiest rock circuses of all time.

You opened to a horde of 100.000 in Hyde Park in London in June and

proceeded to bend every ear in America near the breaking point for two

months cross-country. Though it didn’t last long, it was a fairly vulgar

spectacle (…)". So answers Winwood: "(…) the show was

vulgar, crude, disgusting. It lacked integrity. There were huge crowds

everywhere, full of mindless adulation, mostly due with Eric and Ginger’s

success with Cream and, to a more modest extent, my own impact. The

combination led to a situation where we could have gone on and farted

and gotten a massive reaction. (…) We did not sound good live, due

to the simple lack of experience being a band. We’d had no natural growth,

and it was very evident onstage. (…) We had to break up because that

was the only way we could get out of the whole mess. And it was a complicated

deal (…)." (This dialogue is part of the article titled Steve

Winwood, Rock’s Gentle Aristocrat, which came out in the US magazine

Musician, issue dated October 1982.)

Eric

Clapton talked at length about Blind Faith not too long after that experience

had come to a close, when – his solo career already in motion, as was

the group called Derek And The Dominoes – he was interviewed by Jan

Hodenfield for an article which appeared on US magazine Rolling Stone.

A bitter conversation, as this brief excerpt makes clear: "Well,

it was… it was very frail. That whole thing we did was very transparent.

I mean, it’s almost not there. And in the context of something like

Madison Square Garden where you’ve got many thousands of people who’s

seen hundreds of better bands, or, you know, like Hendrixes in the audience.

And you’ve got this fantastically kind of fragile thing on stage (…).

The minute you get onto the stage in Madison Square Garden, first thing

you think is how to get out. You just battle through, get it over with

as quickly as possible. I think I’d still think that now if I was to

do that gig today."

If

we consider the real reason why the group ended – by nervous implosion

provoked by excessive outside pressure – the way the group had started

appears even more peculiar: as a peaceful, private artistic holiday

for Eric Clapton and Steve Winwood. The former, already acclaimed as

"God" on the walls of London at the time of his being a member

of John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers, was coming out of his intense but draining

experience with Cream: the group had brought improvisation to the stage

all over the world, but a heavy commercial load and the need for the

group to be highly creative every night in a line-up that made the guitar

player especially naked to all kinds of judgments had convinced the

three musicians it was better to stop. Winwood came from Traffic, a

group that – though much-loved – had always remained a "successful

cult"; life on the road was not strange to him – his first big

break as a singer and keyboard player had been with the Spencer Davis

Group, when he was just sixteen; it appeared that the time was right

for new experiences. Bit by bit, Ginger Baker, the flamboyant drummer

that had been such an important part of Cream, had joined the duo.

A

lot of bonus tracks and the precise chronology that together with the

exhaustive liner notes by John McDermott are featured in the rich 2001

Deluxe Edition of the only album recorded by Blind Faith, originally

released in August, 1969, made it possible to determine with much precision

the group’s various stages, from informal jam sessions to the first

original compositions, from the joining of bass and violin player Rich

Grech – a musician who came from the experimental, never much appreciated

line-up of the group Family that had recorded the albums Music In A

Doll’s House and Family Entertainment – to the frantic completion of

their album with the help of the former producer of Traffic, and at

the time producer of the Rolling Stones, Jimmy Miller.

Why

frantic? Because the managers of Clapton, Baker and Winwood (Robert

Stigwood being the manager of the two former Cream members, Island owner

Chris Blackwell of the former Traffic) had already planned a remunerative

tour of the States. Atlantic (in the USA) and Polydor (in Europe) had

already announced the release of an album, to coincide with the tour.

We know what happened: trying to satisfy the impossible request for

a "new Cream" the group had to add to the repertoire a few

tracks that had been part of that impossible-to-be-replicated group.

At that point, it was inevitable for Clapton and Winwood to split the

group.

It

was a pity, ’cause the album had demonstrated beyond all possible doubts

that the relationship between Winwood’s muse and Clapton’s guitar could

produce rich fruits. While Rick Grech’s bass had played the part with

diligence (and maybe a pinch of shyness?), the real surprise had been

Baker: always easy to recognize, true, but with a maybe unexpected flexibility

in his being ready to serve Winwood’s compositions. Winwood – keyboard

player, guitarist and singer – had proved to be the most decisive part

of a band that – quite differently than expected – had appeared to be

more similar to "a new Traffic" than to "a new Cream".

Winwood’s vocals had proved a great match for the tight rhythm of Had

To Cry Today and – thanks also to his Hammond B3 – had given gospel

accents to Presence Of The Lord, Clapton’s composition which was destined

to become a classic. The cover of Buddy Holly’s Well All Right had been

a lighter moment, while Baker’s Do What You Like, besides good solos

by guitar and drums, had showed Winwood’s Hammond halfway between Mike

Ratledge and Jimmy Smith, almost an anticipation of the solo featured

in the Traffic track The Low Spark Of High-Heeled Boys. Traffic came

to mind on the first track of side two, Sea Of Joy, sporting acoustic

guitar and violin. Can’t Find My Way Home, with two acoustic guitars

and drums played using brushes, went straight into the "classic

song" category.

The

50′ of the live concert are really all there is on the DVD. It’s obvious

that given the musicians’ past appreciation of the group’s career asking

them for a contribution was out of the question; but the "extra

materials" are really poor: we have the I’m A Man promo by the

Spencer Davis Group, the promo of Hole In My Shoe by Traffic, and a

brief excerpt of Cream’s I’m So Glad taken from the famous Farewell

Concert; we also have a tiny, absolutely useless piece by Family; a

few words by Winwood; two brief excerpts from those interviews with

Clapton and Baker from Farewell Concert; there’s also a discography

of the four musicians up to Blind Faith. All in all, not much, really.

The

first scenes bring to mind those old pictures: we see Marshall amplifiers

(just a few), a P.A. by WEM (with that red logo), an RMI electric piano,

Ludwig drums with double bass drum, Fender Jazz bass, Hammond B3 organ;

instead of his usual Gibsons, Clapton plays a Fender Telecaster with

a Stratocaster neck. Something funny? After three songs, Winwood leaves

the electric piano and goes to the organ, taking with him the only mike

stand at his disposal. The group members were nervous for sure: a crowd

of 100.000 (we see Donovan, in white, and dark sunglasses; and – if

you blink you’ll miss him – Mick Jagger), first group concert, new songs.

Clapton

is the one that appears to be the most ill-at-ease: the more the expectations,

the more insecure he looks; he appears to be more fluid playing on such

atypical things as Can’t Find My Way Home or on "lighter"

stuff such as the group’s cover of the Stones’ Under My Thumb; quite

a surprise, he looks not too sure about the rhythmic accents of Traffic’s

Means To An End. Grech knows quite well he is "the fourth member",

so rather than to lead, he follows; there are some precious close-ups

of his face that show his satisfaction when he "locks" with

Baker’s drums, or the vibrations of the fourth string when he pushes

harder. Baker is Baker – but it’s a fantastic, educational thing to

watch him negotiating rests, accents, with Winwood, head always turned

to the left (Clapton is in the back); we also have some close-ups of

his shoes on the bass drum pedals; there’s also a (unexpected) passage

for cymbals at the end of the second verse in Can’t Find My Way Home

which reminds us of how colossal were his achievements; all his rhythmic

framework – on this piece, and the others, too – is always conceived

and played with a lot of clarity. In those keys, singing some "beautiful

bum notes" is practically inevitable, but Winwood is his usual

brilliant self; nice comping on piano and organ, nice solos.

First

track is Well All Right, just to get the right feeling. Then we have

Sea Of Joy, without the violin solo. A nice blues, Sleeping In The Ground.

Winwood on organ in Under My Thumb, where Baker looks like he’s having

tons of fun. Can’t Find My Way Home is maybe the best piece here – check

Winwood counting, and directing the dynamics. Do What You Like has a

nice organ solo, and a brief one by Baker (what happened to the guitar

solo?). Even without the wha-wha pedal, Presence Of The Lord is ok.

Then we have the already mentioned Means To An End. In closing, Had

To Cry Today is the perfect mix.

All

things considered, an absolutely indispensable document (especially

so for those who don’t know what we’re talking about).

Beppe

Colli

©

Beppe Colli 2006

CloudsandClocks.net

| Apr. 28, 2006